Pride and Prejudice and Fairytale: Reading Jane Austen's Novel as a Modern Fairy Tale

My honors thesis completed in Spring 2021.

Click here to view the full thesis.

Abstract:

In this thesis, I argue that Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice can be read as a fairy tale that participates in an important tradition of women in storytelling. Historically, fairy tales have been the means whereby women convey important messages to other women through narratives about specific female experiences in the social world. My work establishes Austen’s role in composing a modern fairy tale that has given women the opportunity to voice their concerns over centuries, specifically in regards to marriage, consent, and financial dependence and insecurity. Moreover, seeing Austen’s work as fairy tale allows for a way to speak about the novel’s significant afterlife. Like so many other fairy tales, such as Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, Pride and Prejudice has cross-cultural mutability, evolving over time into various adaptations as it is passed down through generations. YouTube series such as The Lizzie Bennet Diaries (2012-2013) have altered the story to convey their own messages and warnings on topics like consent, offering more modern feminist twists on the classic.

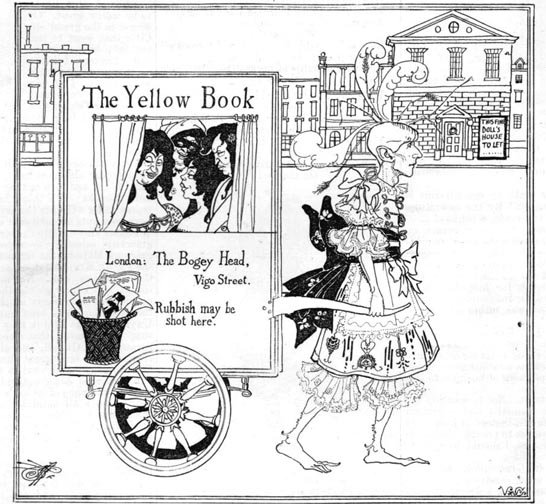

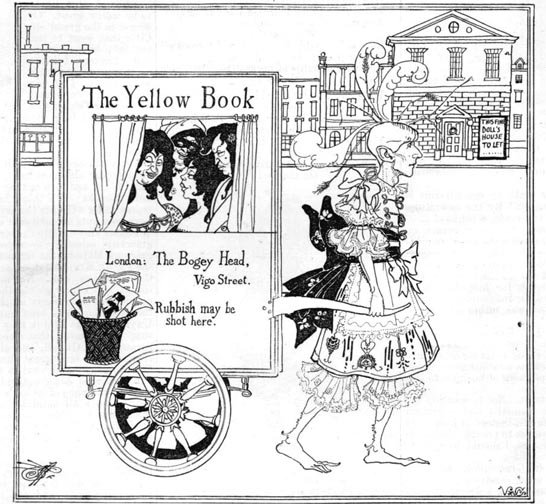

Understanding the Victorian Unfeminine (Journal Article)

Published in the UF Journal of Undergraduate Research in November 2020.

Click here to view the full article.

Abstract:

This article traces concepts of the “unfeminine” in Wilkie Collins’s sensation novel The Woman in White (1860) and Victoria Cross’s New Woman fiction, Six Chapters of a Man’s Life (1903). Both texts feature female characters who defy Victorian standards of femininity: Marian Halcombe of The Woman in White and Theodora Dudley of Six Chapters of a Man’s Life. Despite their unfeminine physical and mental characteristics, both women are regarded as striking models of their sex by their male narrators. I examine these characters’ unfeminine appearances and heightened intelligence in terms of arguments made by Victorian physiognomists and sexologists to suggest that the biological and intellectual parallels between Marian and Theodora establish a pointed resistance to Victorian ideals of “womanhood.” I argue that in Sensation and New Woman fiction, we see the emergence of the “unfeminine” woman as the embodiment of a radical desire for defiance during a transformative age.

Confessions of a Gator Abroad (PRISM Article)

Article originally published in the Fall 2020 Edition of PRISM: UF Honors Magazine.

Amidst the chaos and uncertainty that has been 2020, I made what perhaps could be called an usual decision: I decided to go ahead with my exchange program this Fall, and spend several months studying in Scotland. Since September, I’ve been taking English and Scottish Literature courses at the University of Glasgow, through UF’s College of Liberal Arts and Science’s Beyond120 Exchange Programs. When I decided to go abroad, it was back in February, when coronavirus was only a distant concern. Once everyone went home in March, and summer study abroad programs were all cancelled, it seemed likely that Fall programs would be next. There was a lot of anxious waiting that summer, watching case numbers in the U.S. and the U.K.

Finally, in August, the Fall programs were given the go ahead. For me, the choice ultimately came down to taking UF online classes at home, or taking online classes in Scotland. I decided that I would be safer in Scotland, considering Florida’s high COVID-19 numbers, and that I’d at least have the possibility to travel and meet new people. So, at the end of August, my best friend and fellow UF student, Sasha, and I flew over to Glasgow. Following the UK coronavirus guidelines, we had to quarantine in our dorm for two weeks, so we made sure to arrive early before classes began. Quarantine was probably about as interesting as you would expect--we would have groceries delivered, and I focused on reading, and trying out new hobbies like embroidery. Since we moved in way before anyone else had arrived we even threw ourselves a karaoke night!

Then, classes began September 21st. I’m taking three courses, and have class just two days a week. They consist of hour or hour-and-a-half long seminars that are all via Zoom, where we discuss our readings and the lectures we’re expected to watch beforehand. Even though they’re online, they are still enjoyable, and there’s definitely a big difference between UK and US classes. I only have 3 assignments overall in my courses, plus a participation grade, which means while there’s arguably more free time, the few essays and other classwork are worth a larger percentage of the overall grade.

In terms of living in Scotland, the country has imposed tighter coronavirus restrictions after cases increased when university students returned. In Glasgow, in addition to wearing face masks and social distancing measures, visits to different households are prohibited, and all restaurants now have to close by 6 p.m. The University of Glasgow did have an outbreak in several of the dorms at the beginning of the semester, with many students having to self-quarantine. Thankfully our residence hall wasn’t as badly affected, and now the number of student cases is starting to decrease.

With all of this going on, probably the biggest question I get asked is if I’m still glad I came to study Scotland. Admittedly, there are downsides. All the classes and various organization meetings are online, which isn’t ideal when you came to experience a different university environment. It’s sad to walk past the beautiful buildings on the campus, and see them with empty and darkened windows, wondering where my classes would have been and what the classrooms would have looked like. Glasgow is known for being a vibrant city, with concerts and other entertainment, so it can be difficult knowing so much of that has been cancelled or postponed, especially when you hear how usually there are ceidleighs (pronounced cay-lees), or Scottish social gatherings with country dances, all the time.

However, being abroad is amazing, and I do believe traveling to Scotland has still been a worthwhile experience. The people in Glasgow are super friendly, especially our flatmates, who are all from different areas of the U.K. It's also so special to experience Fall (my favorite season) in a place where you can actually see the leaves change. We live in a gorgeous Victorian neighborhood, and the fastest way from our residence into the city’s West End is through the beautiful Botanic Gardens, which are always filled with people walking dogs!

I think my favorite part has been the ability to explore the city and travel around the country. While we are not allowed to travel to continental Europe because of the American travel ban, and England recently went into lockdown, we can still travel in Scotland, which is filled with many amazing cultural and historical sites. Besides exploring the museums and other attractions in Glasgow, we’ve visited places such as Edinburgh and the Highlands.

Edinburgh was one of the most beautiful cities I’ve ever visited--it has gorgeous historic architecture, and its hills allow you to see the surrounding mountains and views of the ocean from practically everywhere. Plus, it’s pretty amazing to look up and see Edinburgh Castle sitting on an overlooking hill while you’re walking around the city, and hearing bagpipes from local street performers. It’s also a must-visit for any Harry Potter fan (regardless of your current opinion of J.K. Rowling). We took a tour that not only showed us the cafe where Harry Potter was originally written, but also the graveyard that inspired many of the names used in the series, the most notable being Tom Riddle, a.k.a Lord Voldemort.

Then, we travelled north to the Highlands to ride the Jacobite Train, a.k.a the Hogwarts Express from the Harry Potter films. It's famous for its scenic route past Highland mountains and lakes, and the praise does not do justice to the stunning scenery--At one point I even saw deer grazing on a mountainside! I definitely recommend it for anyone traveling in Scotland. While we have to be cautious in planning future travel, we hope to travel north again to see the Northern Lights this winter.

While of course this isn’t the ideal time to be studying abroad, I believe it’s always important to seize experiences while we can--especially when we’re students. When I made the choice to go abroad, I asked myself: “When am I going to get another opportunity to live and study in Europe again, especially as I’m now a senior?” While I do wish that I could be here under normal circumstances, I’m so thankful for all the special experiences this program has afforded me. Besides, years from now I can look back and say I spent a semester abroad during a global pandemic--definitely a sentence I hope I’ll never have to say again. And yet, carpe diem!

What's New with Honors? (PRISM Article)

Originally published in the Spring 2020 edition of PRISM: UF Honors Magazine.

2020 has brought many new and exciting developments to the Honors Program, the most recent being a move to Walker Hall. But what else is up with Honors, and how are we growing in this new decade?

Growth in Applicants

The Honors Program has seen a considerable rise in applications, and while the Honors Program is still planning on admitting the usual amount of students, it is a good indication of the rising interest in Honors at the university.

“This year we had almost 2,000 new students apply compared to last year, so applications are up from 9,300 to 11,000 and some odd,” Dr. Mark Law, the Director of the University of Florida Honors Program, said. Due to the increasing number of applicants, Law believes the Honors office will see growth in the test scores of incoming students.

Growth in Staff

In addition to the new Honors academic advisor, Dr. Renee Clark, the Honors Program has added new members to the 2020 team: Coordinator of Marketing and Communications, Jess Berube, and Magda Wahl as the new Office Manager. The Honors office has also just hired another advisor, Michael O’ Malley, who is coming to the Honors Program from the UF College of Engineering.

“The staff supporting is growing,” Law explained.

Growth in Course Offerings for Honors Students

“Our class offerings have really grown,” Law said. This semester, the first sections of honors biology became available and have been popular choices for students in the Honors Program. Law also explained that this upcoming fall, unique Honors sections will only further increase, as the Honors Program plans to offer an Honors Arabic course. Traditional (un)common reads and (un)common arts are continuing to expand as well.

“(Un)common read enrollment is still really strong,” Law said. “It was up spring this year compared to spring last year. In the fall we’ve got forty-seven (un)common reads being offered, so there are lots of new course offerings for students to take advantage of and get involved with.”

Another exciting and special course offering centers around student-run Honors classes. Usually (un)common reads, students can approach the Honors director and explain that they are interested in teaching a certain book.

Students then need to find a faculty mentor for the course, with expertise in the subject area the student is covering, not only to offer backup and assistance for the class, but also to ultimately handle the final grades. After securing a faculty mentor, Honors students can lead their own Honors (Un)common Read. Currently, two student-run Honors classes will be offered in Fall 2020, and Law explained that they hope to further formalize the program over the next year, including establishing an application process for juniors and seniors who want to lead courses.

“It is a great opportunity if you are thinking about going to grad school,” Law stated. “Having some teaching experiences ought to be a real plus to getting into grad school and helping to find a program, so I think it can help students a lot.”

The Honors Program is also beginning to work on an idea that falls partially under advising, and partially under course offerings. Aimed at first-year Honors students, it would help these individuals navigate the numerous and often overwhelming opportunities available to them in many different areas at the University of Florida.

“I think it’s particularly overwhelming for our first-year students to try and decide, do I want to be an Intersection Scholar, or what is International Scholars, or do I want to do research?” Law explained. “We’re going to try and work out ways to help first-year students figure out where they need to go and what the opportunities are. I think over the next year we’re going to get that a lot more put together and formalized.”

Growth at Walker Hall and the new Honors Residential Hall

At the previous location of the Honors Office at the Infirmary, the Honors Program had very limited space—during almost all of 2019 two Honors Program staff had to work remotely at Little Hall. Now, the Honors Program has fifteen office spaces at Walker Hall, compared to the previous seven at the Infirmary, which has allowed the Honors Program to accommodate the newest members of their staff.

“We were really crammed in the Infirmary, and had people scattered, so it’s nice to be all together again, in the same workplace, and with some room to grow,” Law said.

While no new updates are currently planned for the stately building across from Plaza of the Americas, there could be some remodeling in 2021. However, Law expressed that there is hesitancy to renovate the space, as the Honors Office could be moving to the first floor of the new Honors Residence Hall in only a few years, as it is scheduled to be finished in Fall 2023.

Besides providing access to Honors advising and the Honors Office all in the same residential building, Law explained other hopes the Honors Program has for the new residence hall, such as adding in numerous classrooms in order to offer even more Honors courses.

“I’m hoping in the new building there’s a lot more of those kinds of spaces, and we can do even more classes right there, where the students are living,” Law said.

More study spaces and common room areas are another desire for the new building.

“I love the common room layout, so we would want to have more of those spaces in the new residence hall, but I would want more study spaces like the one adjacent to the [Hume] classroom, where small groups can get together” Law said.

Growth in Honors Travel

The Honors Program designed a new pre-health Honors study abroad, which will be offered to students in the future: UF in Thailand will allow students to study the intersections of traditional and modern healthcare in Chiang Mai, Thailand. For other Honors students interested in future study-abroad opportunities, another Honors-oriented program includes one on the Holy Roman Empire. Dr. Law also explained that although not specifically designated as Honors, the UF in Cambridge program is a study abroad that usually is almost always made up of Honors students.

But study abroad programs are not the only opportunities the Honors Program is providing Honors students who wish to expand their learning through travel. One such example is the Signature Seminar, Hamilton’s New York, taught during spring break of the Spring 2020 semester. While in New York, students learned about the life of Hamilton and the history of the American Revolution by visiting landmarks such as Federal Hall, Trinity Church, and the Alexander Hamilton Grange National Memorial. The Honors Program only hopes to offer more short Honors excursions, like the New York seminar, in the future. Law explained that the New York trip will contribute to figuring out the logistics of similar future programs, along with deciding what is possible for these programs and how it will work.

“I’ve got a faculty member that’s interested in taking some students up to Birmingham, Alabama and doing civil rights. I could see going to an art museum in Chicago or New York. So I think there’s lots of opportunities to do city explorations, with cities as texts, where you can go off and explore certain topics and do a shorter trip,” Law said.

Another added benefit of these programs is since they focus on traveling within the United States, and are for shorter periods, they will be considerably more affordable than study abroad programs.

“New York is expensive, but it’s still cheaper than going to London or Paris,” Law said.

Law further explained that these Signature Seminars would be planned during breaks, such as spring break, or during times like the first week of May, which is usually after commencement. This would allow students with upcoming summer obligations, such as internships, to attend these programs before their other summer requirements begin. December is another possible option, as there is about a week between when finals end, and the start of the holidays.

“I think you could do a three or four day trip, and still not feel like you’re impinging on family time for students to go home and visit with mom and dad,” Law said.

Depending on the timing, the Honors Program might even plan an excursion after New Years.

Growth in Scholarships for Honors Students

In discussing these Signature Seminars in American cities, Law stressed the Honors Program’s desire to provide more potential funding for students interested in these types of programs, along with study abroad.

“We’re definitely trying to actively fundraise for scholarships,” Law said. “I am particularly fond of scholarships that support experiential kinds of activities, something that could offset the trip to New York or study abroads.”

Many Honors students apply to study abroad, but study abroad programs can have considerable price tags, even with Bright Futures, between the cost of programs, plane tickets, and basic living expenses. While the Wentworth Scholarship, offered by the Honors Program, provides $1,500 towards summer study abroad programs, Dr. Law explained that the Honors Program would like to do more:

“I think we could use and give a lot more study abroad scholarships. There’s obviously a ton of honors students going abroad, and if we could support that and help, that would be great,” Law said.

Another area where Law would like to provide more scholarships for students over time is in offsetting the housing costs for Hume Hall. Hume Hall, while it is the official Honors Residence Hall, is also one of the most expensive residential halls on-campus, and can therefore be too costly for some students in the honors community to afford.

“We do a lot of great things in Hume, and students that want to live there but can’t afford the price differential is another area where I would love to get some more scholarships,” Law said. “We are actively working on lots of opportunities there to try and support students, and hopefully we’ll have some big time successes.”

Roundtable: Inside Look at the NAVSA Academic Conference (PRISM Article)

Originally published on the PRISM website on November 5, 2019. Co-written with Katherine Jovanovic.

Link: https://ufprism.com/2019/11/05/roundtable-inside-look-at-the-navsa-academic-conference/

The North American Victorian Studies Association (NAVSA) Conference took place in Columbus, Ohio from Oct. 17-19. The annual conference invited scholars to present research on Victorian literature, history, or art history related to the theme Media, Genre, & the Generic. Each day included four 1.5-hour panels in both the traditional and roundtable style. Among the attendees from UF included Honors students and PRISM members Hannah Calderazzo and Katherine Jovanovic, both of whom presented in the undergraduate poster session.

For the poster session, undergrads created 4×3-foot posters to display their research. These posters were then set up in a long hallway adjacent to the panel rooms. Students would then stand by their posters, and academics could walk around and ask questions. In this article, Calderazzo and Jovanovic will give a behind-the-scenes look at an academic conference through a roundtable-style dialogue.

Which panels were your favorite?

Hannah: I was surprised to find that my favorite panels were the ones on Neo-Victorianism, which deals with examining modern-day interpretations of Victorian England/Victorian novels. For example, one of my favorite presentations was “‘I’m merely an observer of men’: Gender, Agency, and Genre in The Woman in White (2018),” given by Jennifer Camden from the University of Indianapolis. In her presentation, Camden discussed the most recent BBC miniseries adaptation of Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, starring Ben Hardy. She tied the BBC mini series back to the #MeToo movement, discussing how the characters were sexualized in the adaption—as they were portrayed as far more attractive than their novel counterparts. Wilkie Collins’s novel is also notable for its complete lack of sex; Meanwhile, the mini series not only adds passionate kisses and scenes of sexual tension, but also scenes of sexual violence and abuse. Although filmed before the #MeToo movement, it was released afterwards, prompting scholars to ask, “Why add so much sexualization to a sex-less novel?” Another fascinating presentation was “Not Just a Ghost Story: Crimson Peak and the Neo-Victorian Gothic” by Sylvia Pamboukian from Robert Morris University. In her paper, she gave an overview of how Crimson Peak utilized Victorian supernatural and gothic tropes, such as incest, ghosts, and a decrepit house. Yet Crimson Peak also brings itself into the modern era with its grotesque phantoms, which differ from the typical pale spectre. Dwelling on the ghosts, Pamboukian argued that despite their monstrous appearance, they are women seeking to aid the heroine of the film, giving it a more feminist twist than the average Victorian tale.

Katherine: I also saw some similar feminist twists in my favorite panel—a roundtable called “Decadent Women, Aestheticism, and Genre.” For instance, Nicole Fluhr (Southern Connecticut State University) spoke about Vernon Lee’s undisciplined prose, as in the 1880s she turned away from traditional historiography and reimagined her work through aesthetic subjectivity. For example, she called her research “scattered, impressionist work,” which added an element that suggested refusal of mastery of knowledge, which ultimately encouraged inquiry. Fluhr argued that this aesthetic subjectivity manifests in Lee’s “Dionea,” a story where an Italian doctor wishes to write the fate of the pagan gods, but unbeknownst to him, he is actually raising Dionea, the incarnation of Aphrodite. He fails in his endeavor to write out the history, and he ironically never takes Dionea’s telling of myths seriously. Through this analysis, Fluhr posits that Dionea herself functions as a budding aesthetic critic. I love thinking about the relevance of retelling mythology, which has happened even before the nineteenth-century up until now. It especially ties in with Lee’s notion of her research as “not even fragments but impressions,” which underscores how history cannot always be objectively captured on paper in words. Rather, I think it keeps evolving from these “impressions,” and resurfaces, as represented in intuitive and mysterious figures like Dionea. Maybe we can’t always understand history, but it always lurks beneath our present surface.

Was the conference what you expected it to be?

Katherine: I didn’t expect the conference to feel like a community. I thought it would be formal in a daunting sense, but since many professors and scholars knew one another, it was evident they just wanted to share their research and have open, intellectual conversations. The keynote speakers really surprised me because they did not address conventional Victorian topics. The first keynote speaker, Priya Satia, Professor of History at Stanford University, spoke about the evolution of historical imagination, and she covered historical events before and after the Victorian period (what she called a Victorian sandwich). For example, she shared how the perception of guns in the late-eighteenth century as a sign of self-command allowed a Quaker family like the Galtons to sell them without any criticism from the Quaker community. However, in the 1790s, once guns were criticized for their role in perpetuating slavery, the Quakers, who held anti-slavery beliefs, turned against the Galtons. In response, Galton published a treatise to justify his business in selling arms, arguing that everyone is ultimately complicit in causing war, so his gun business was no different. The second keynote speaker, Mike Leigh, directed films such as Topsy-Turvy, Mr. Turner, and Peterloo. It amused me to see how many scholars in the audience tried to pick apart his films and search for “meaning” and “intent,” whereas Leigh ultimately focused on artistic imagination and production that occurs in the moment of filmmaking.

Did you have a favorite audience question from the keynote panels?

Katherine: I can’t remember the exact question, but one of the audience members asked Leigh about the research required to make a film like Peterloo, and Leigh, in his brilliant way, dodged the question and rather expressed that no matter how much research you do or how many history books you read, only doing that doesn’t produce a film. A lot of what transpires emerges in the moment of shooting on location with the actors. That’s what makes a film come to life. I think that’s really crucial in remembering that the figure of the director or the author is not an omniscient genius that simply pulls the film out of his or her head. There are multiple facets to artistic production and not everything can be planned or have grand meaning behind it. If that weren’t the case, films would lose organic, genuine feeling.

Hannah: He did that a lot. Remember when one person stood up and mentioned how he had included an obscure historical figure in one scene of Peterloo? The audience member was so enamored with the idea that that he had put it in the film as a special “easter egg” for Victorian scholars. To which Leigh quickly responded along the lines of “No, I did not do it for you.”

How did this conference compare to the one last year?

Hannah: I personally enjoyed this conference more than the one last year, but I think a main factor was traveling to a completely different state, rather than just staying in Florida. Being in Columbus was especially fun because of the crisp fall weather, where it was chilly and the leaves were gorgeous colors. In terms of the actual conference, I thought the undergraduate workshop, where we discussed our topics with one another, was more relaxed and enjoyable than the one last year. I think this was a combination of there being more undergraduate presenters, 20 compared to last year’s eight, and the fact that it was not the first time they had offered the undergraduate poster session. I feel like this contributed to a reduced feeling of nervous tension about creating perfect “elevator pitches,” or short summaries to go along with our posters.

Katherine: I really liked how we scrapped the concept of the “elevator pitch” in the workshop because that can feel so formulaic when you’re presenting research. I remember Nathan Hensley (Georgetown University), our undergraduate workshop leader, told us to think of it as a “live electric wire” to create “research in motion” when we spoke to people. It’s much more approachable to hone in on key words and get at the heart of your argument and see how the person interested in your poster responds. Then, you can fall into a natural flow of conversation that leads you to new pertinent research angles.

Hannah: Especially since the first panels officially began at 8:30 a.m., so if you wanted to attend all the panels, or if there was one you really wanted to see during that time slot, you had to wake up fairly early. It also didn’t help that we stayed up late after leaving the keynote speeches a little after 6 or 7 p.m.. You needed to get dinner and then relax, so usually you might be up until 11 p.m. or later. To use a colloquial phrase, the grind also did not stop, as we did have homework due during the conference.

Would you attend NAVSA again?

Hannah: Oh 100%. While I’m not completely certain about attending graduate school, I love being in the academic atmosphere of NAVSA, where you are surrounded by people who love a subject, and are so eager to talk with you about it. It’s also wonderful as an English major to feel a sense of community and support—to tell someone you’re an English major and not be met with a polite, “Oh really? How nice,” but rather hear, “That’s amazing! What are you studying? What are you especially interested in? What are your favorite books?” etc. No one questions your major because everyone else is an English academic, graduate student, or historian, and they are all so kind and uplifting.

Katherine: That’s so true. It’s also comforting when they tell you they hadn’t done this caliber of research in their undergraduate careers. It makes you realize that there’s still a long way to go and change as a person, no matter what you want to do.

Do you have any advice for someone who might be interested in attending NAVSA, or a similar conference?

Katherine: I would reach out to your professors because they’ll know which conferences are best for undergraduate students, either for presenting at or attending. You also don’t have to travel far to get a glimpse into what an academic conference is like. There are conferences at UF like the UF Conference on Comics, but I think no matter which conference it is, participating in one at the undergraduate level shows tremendous dedication and interest that sets you apart.

Hannah: Definitely. I was fortunate enough to attend NAVSA last year because one of my instructors reached out to a number of her students and told us about the opportunity. From there, it was a matter of thinking of a topic and writing a proposal. After submitting my abstract, along with a letter of recommendation, I was eventually accepted to the conference. It is certainly important to keep in mind that participating in a conference in your field of interest is entirely possible for anyone who truly desires to attend.

Hollywood's New Comfort Zone of Superheroes, Sequels, and Remakes (Opinion Article)

Originally published in the Fall 2017 edition of PRISM: UF Honors Magazine.

Despite Hollywood being on a superhero binge, the summer 2017 box office finished as the lowest in over a decade. Not too long ago, audiences were smitten with book-to-movie adaptations of dystopian societies featuring rebellious teenage protagonists fighting off oppressive evil entities. Now the movie industry is dominated by big-budget superhero films that continuously crank out sequels and remakes. Despite these hit movies such as Wonder Woman, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol.2, and Spiderman: Homecoming, many other films fell flat, causing the summer to conclude with only $3.8 billion in earnings. While this may seem like a large sum, it is in fact a 14% decrease from last year’s box office profits.

A possible reason for this summer’s decline is because of Hollywood’s recent trend of constant reboots and sequels. This past summer box office saw continuations such as Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, Transformers: The Last Knight, Despicable Me 3, and Cars 3 all pull in series lows. Franchise reboots such as The Mummy, starring Tom Cruise, completely flunked in theaters, with the movie earning only $80 million domestically despite its $125 million budget.

Sasha Vagos, a UF telecommunications freshman, noted, “It demonstrates the lack of originality in Hollywood today. The movie industry believes that in sticking to what the audience enjoyed before, they’ll be successful again; but clearly the public is tired of seeing the same things.”

This summer’s box office performance poses the question: Has Hollywood lost its ingenuity? While the movie industry occasionally launches a unique film, it seems for every original story they generate a dozen sequels and remakes. In fact, Walt Disney Pictures currently has up to fourteen remakes planned of classic films such as The Lion King, Mulan and Aladdin. Has Hollywood run out of ideas? Or has it merely become lazy in its approach to what they believe audiences will appreciate.

Marvel at least attempts in many of its films to create new storylines and add complexity to classic heroes, mixing in clever humor to balance more serious scenes. Marvel has also performed well because of their embrace of diversity, a factor many audiences are prioritizing. Baby Driver, Mother! and Get Out are also among the unique movies that riveted audiences this past year. Despite these successes, studios commonly produce series that follow a lurking pattern in which there’s a lack of strong writing, reliance on old content, and characters who have little to no depth. They make no attempts to build on the previous stories, or put a unique twist on classic tales. Instead, they merely go through the motions of assembling a movie they hope will pull in millions.

Studios are afraid to invest in smaller, original films because of the risk. It’s a toss up if the movie will be beloved by audiences, or completely flop. Rather than take a chance, studios cower in the comfort zone of blockbusters. They put millions behind these movies, because big-budget mega films have consistently performed well over the past few years. A skulking trend among studios is that if these movies perform well, a sequel is inevitable. Studios believe the public liked the movie so much that they definitely can make more money if they make a sequel or reboot this franchise. While some studios such as Marvel are able to successfully accomplish this formula of reusing and recreating superhero films, other companies are not so fortunate.

These repetitive aspects in many of the enormously popular superhero films call into question if audiences actually want original movies, or if they are content with predictability. In some ways it seems like audiences are satiated by knowing what to expect from a superhero film. They know it will feature a ragtag group of heroes facing a villain who threatens the world. With quick-thinking, the hero’s skill set, and a bit of humor, the villain is defeated, and all is saved. Then there’s the jerk with a heart of gold, a superhero film’s favorite, the classic character whose bad habits or nature is secretly hiding a kind and caring personality, such as Tony Stark or Batman.

Formulaic movies both inside and outside the superhero universe are struggling. Continuous sequels from children’s animated features and reboots of older movies have performed poorly, and seem to indicate a restless audience that is ready for change. The blockbuster comfort zone that studios have hidden in for so long is beginning to collapse. Audiences’ infatuation with Marvel and DC movies will soon also fade and they will turn their attention upon a new trend.

Hollywood needs to force itself out of its crumbling palace of big-budget films and evaluate the establishment of fresh, innovative movies. Studios are creating entire cinematic universes, a phenomena never before seen, but at what cost? Smaller, more one-of-a-kind films are being crushed under the behemoth of sequels and reboots. In the future, do we really want to live in a world where we are constantly bombarded with continuations and revamps, and excellent, independent films such as Get Out have no chance of survival? We must assess for ourselves if Hollywood’s current obsession with enormous movie franchises are worth the future consequences.

Here, There, and Everywhere (Poetry)

Poem originally published in the Spring 2018 edition of PRISM: UF Honors Magazine.

Here, under these skies, I know who I’m meant to be

There is a certainty in myself, but

Everywhere that I’m with you I am lost but somehow free

Here, with you, I am me, but not me?

There is no greater joy than seeing your smile

Everywhere your light breathes, it is there, not

Here that I wish to stay for a while

There, with you, I’d go a thousand miles

Everywhere else I am somewhat alone

Here in this place that can be cold as stone, but

There, where I am also my own

Everywhere with you I feel beautiful and known

Here, There, and Everywhere with you I may be, but

Here, There, and Everywhere I am also with me

The Woman in Red (Prose)

Presented at the 2019 Luminaire Fine Arts Showcase at the University of Florida.

The icy wind whipped through the slumbering trees. Freshly fallen snow lay glittering upon the ground and nestled in the nooks and cusps of the outstretched boughs. The stark contrast between the rich, dark oaks and pure, alabaster snowfall attracted the attention of the young woman who wound her way among the meandering paths.

Shivering, she pulled her scarf higher upon her lips, releasing a sigh. It was only here in the depths of the park that she could forget the world that lay just beyond its boundaries. Deep down the trails and twists in this artificial forest, she was concealed from the glare of bright lights, the blare of horns, and the laughter of a joy that was all too false.

Sitting on a nearby bench, she glanced downward at the pale hands emerging from the bright red sleeves of her coat. They seemed so sickly compared to the crimson surrounding them, making her wish that she could assume the dulled palette of the world around her–that she could sink into the soft grays and never emerge. Perhaps become one of the many pigeons, so she could soar through the winter world, instead of watching it as an outsider.

Red. She tugged at the hem of the sleeve. Red as lipstick on a pair of smirking lips. Red as the stain those lips leave behind on a slender champagne glass. Champagne flows, bubbling and overflowing, its sweetness leaving behind a bitter aftertaste. Laughter bursts out, bolstering and bright, but it has a hollow ring . Faces blend and blur, each one smiling with too-white teeth.

Shuddering, she pulled her coat tighter around her shoulders, trying to shut out the images and colors that swirled behind her eyes–the world that awaited her beyond this sanctuary. A hand on her waist, clinging too tightly. A man whose grin was too wide, his teeth blinding.

Stop.

She opened her eyes, taking deep breaths, watching it burst out and curl into fog. She felt like plunging into the snow, to let the cold remind herself that this was reality. Reality was just as much this place of ice, snow, and trees. Reality was here, in this park. Reality was not the city peering in, with thousands searching for what they could not possess in the bottom of a glass, the pounding of piano keys, one too many kisses in the blanket of night.

She stood and kept walking, walking as fast as her legs could carry her, the trees blurring, figures passing by meaninglessly. She only stopped when her lungs burned and her legs were shaking, feet aching in her heels. She was unsure where she was, but the snow still shimmered on the ground, the trees still stretched up impassively.

A couple moved past her, catching her eye. They gave her small nods, polite and cursory. She couldn’t help but turn to watch as they walked away from her. Their coats were dull brown, like the earth. What did they think of her? The woman in red, amidst the rocks and iron lampposts.

As the couple strolled further, she saw the girl stumble, but the man caught her before she could fall, his steadying hand on her elbow. Even from this distance, she could see the way that he looked at her, with a small, close-lipped smile. But in that expression was more sincerity than she had witnessed in ages, so much so that she felt tears prick her eyes, even as the cavernous longing in her chest threatened to consume her.

She stared up at the sky, around at the park that enclosed her, shielded her, cradled her in its cold desolation. She reached out to the trees and placed a steadying hand on the bark, the uneven surface pricking the soft skin of her palm. Perhaps everything could be found here, in this fragile world of ice and snow. Perhaps all the answers were here. But until she knew, knew for certain, she would remain the woman in red, in the depths of a grey-white world.

Rain or Shine (Prose)

Presented at the 2019 Luminaire Fine Arts Showcase at the University of Florida.

He turns to me, grinning.

“What is your favorite weather?”

“My favorite weather?” I reply skeptically. “Not favorite season, or month of the year?”

“No, weather. Y’know, wind, rain, or shine? Your favorite type of weather.” He glances up at the sky as he says it, where the sun beats down impassively, uninhibited by clouds.

“Ummmm… I don’t know.” I answer, pulling my sweater tighter around my shoulders. Despite the bright sun, the mid-October weather is chilly. A fallen leaf rushes past, skittering on the sidewalk pavement before it crackles off into the distance.

“Oh come on. Everyone has a favorite kind of weather. Just think about it.”

“Alright,” I consent, my mind wandering, pondering the obsolete question of my favorite weather.

He reaches toward the sun with both hands, casting a black mask across his eyes. “My favorite weather is sunny. It’s bright, and it’s warm, most of the time at least.”

I curl my toes in their boots, knowing I’m close to an answer.

“It’s like… a big smile, you know? Like when you see someone and they make eye-contact with you, and then a huge grin spreads across their face. You know they’re happy to see you.” He finishes.

“Mhm,” I hum noncommittally. Smiling suns are furthest from my mind.

“Sooooo, favorite weather?” The question is persisted with a kick at the damp leaves under our feet. The swirl of soggy yellows, browns, and russets look up at me when I finally respond.

“You know that time, right before it rains?”

I can tell he wasn’t anticipating this response. He blinks, then gives a small nod. “I think?”

“The air is still a little warm, but now there’s a breeze. It stirs the trees and makes the temperature feel pleasant. The sky is grey, but it’s a pale grey. It isn’t an ominous black or that stormy grey. It makes it calming instead of disheartening, especially since the clouds don’t completely obscure the sun. There are still some places its light pokes through. The calm before the storm, I suppose. Rain is coming, but maybe not for a while. That’s my favorite weather.” I conclude with a brush of my hand on my jeans.

Above me, the final leaves who still cling to the spindly branches flutter softly in the wind. Clouds have begun to drift over the sun. Maybe, just maybe, rain will come.

Red Carnation (Prose)

Originally published in the Spring 2020 edition of PRISM: UF Honors Magazine.

“Spinning round and round we go!

Blackened rose for endless woe,

Yellow iris for hope so bright,

Carnation for chosen love tonight!”

The children fell into a circle, giggling amongst themselves. Their flower crowns now hung askew on their foreheads, petals and leaves tangled in their hair. They resembled forest sprites, back from a night of mischief and magic.

Smiling, Clarissa returned to weaving the long line of daisy chains between her fingers, braiding one bright green stem to the next. It was only the second day of the spring festival, but already the chosen field was strewn with flowers, the floral vendors draping their carts and canopies with flowers of every variety--roses, lavender, honeysuckle, and many more bloomed in the air, releasing their sweet, bright scents.

“Clarissa! Clarissa!” A voice yelled ecstatically. Looking up, Clarissa saw her little sister Violet bounding across the field, long skirts clutched in-hand. “Violet, slow down!” Clarissa laughed, pushing back the broad brim of her bonnet. “But Clarissa!” Violet exclaimed, “There’s a hundred thousand flowers, and there’s going to be a million more at the Rose Ball tomorrow evening. There’s even a rumor that the Prince himself will be the Fae King!”

Clarissa rolled her eyes and tossed the daisy chain around her exuberant sister’s neck. “Just because the Rose Ball is a masquerade party does not mean that the Prince himself is coming in disguise. You dream too much.”

Violet huffed. “Well, at least you get to go! Mother refuses to let me do anything--even if it means I could marry the Fae King.”

“You can marry the Fae King when you’re older. I don’t think twelve is quite a marriageable age.”

“So you say,” Violet pouted, “but everyone knows the Fae like to choose beautiful young maidens.”

“Emphasis on the young, I see,” Clarissa retorted, gathering up her skirts and rising from the ground. The pleasant spring sun had drawn more crowds today than before. Many young couples were walking through the park, the women clutching parasols as bright as the bouquets in their gloved hands, and the men shielding their eyes from the sun with their top hats.

“Oh! Well fine! But if you don’t tell me everything that happens tomorrow, I’ll never forgive you as long as I live!” With that Violet darted away into the crowd. “Violet!” Clarissa yelled. She grabbed her own parasol and went to catch her sister, when she felt something fall from the ribbon of her bonnet and onto the ground. Startled, Clarissa looked down to see a bright red carnation looking up at her through the blades of grass.

She barely had time to question how Violet had placed the flower on her hat before she grasped the carnation and ran into the crowd, following the sound of her sister’s bright laughter… Not noticing the gentleman staring after her, his features obscured by a midnight blue mask. His eyes followed her briefly, before a sudden breeze stirred up a flurry of flowers, and he vanished.

Clarissa felt her chest heaving, constricted by the tight bodice after racing several paces after her sister in a most unlady-like fashion. “Violet! You can’t just go running off like that!”

But Violet merely giggled, clutching a handful of flowers. “I saw him!” She crowed triumphantly.

“Saw who?” Clarissa demanded, growing slightly more annoyed with her bouncing sister.

“I saw him! The man in the mask!”

“Oh, don’t be ridiculous. There’s no one wearing masks here.” Clarissa sniffed. “Your fancies about the ball are running away with you.”

Violet only smiled more, and taking the red carnation from her sister’s hand, neatly tucked it behind Clarissa’s ear.

“Carnation for chosen love tonight!” She sang, skipping through the forest, while Clarissa sighed and followed, ignorant of the singing breeze that spun Violet’s melodies around her ear, and dropped another red carnation onto her hat.

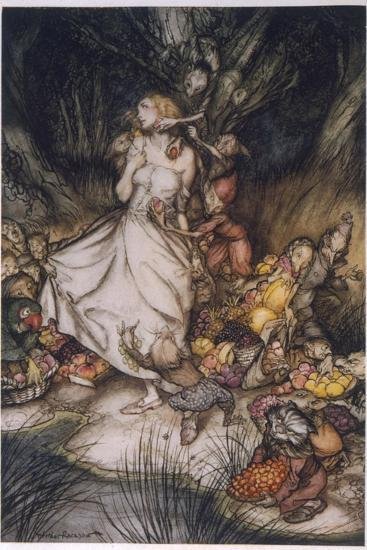

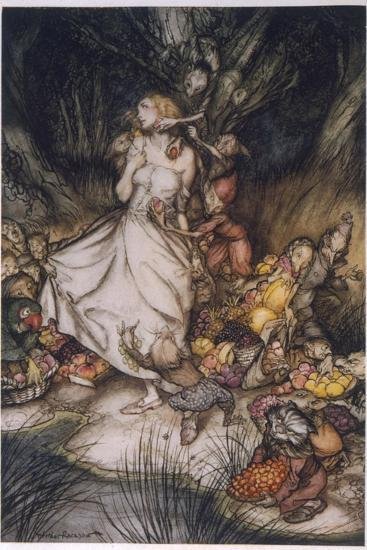

'There is no Friend Like a Sister’: The Reclamation of the Fallen Woman in ‘Goblin Market’ (Essay)

Originally written as a midterm essay for the course “Realism and Fantasy in Victorian Literature” at the University of Glasgow in Fall 2020. Please note all spelling, punctuation, and citations are formatted according to requirements at universities in the United Kingdom.

‘There is no Friend Like a Sister’: The Reclamation of the Fallen Woman in ‘Goblin Market’

Christina Rossetti’s ‘Goblin Market’ (1859) remains one of the most striking examples of Victorian fantasy and sisterhood. However, ‘Goblin Market’ serves as more than just an unnerving and entertaining tale—it represents the reclamation of the fallen woman narrative, and a departure from male-dominated voices and canon in poetry and fantasy. This essay explores how Rossetti’s poem critiques social efforts during the 1850s and 1860s that purposefully blamed and controlled women. Then, it demonstrates how ‘Goblin Market’ moves away from male control, both in its form and utilization of fantasy, before concluding that in a male-dominated society that seeks to destroy women and their reputations, it is women who must step forward to protect their fellow sisters.

When ‘Goblin Market’ was published in 1862, numerous discussions and debates were occurring about women and sexuality, with topics ranging from prostitution to sexual assault. In 1857, William Acton published Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects, offering one of the first pragmatic reports on prostitution in mid-nineteenth century England. As opposed to believing prostitutes were irrevocably immoral, he took a more sympathetic stance to their plight, arguing it was ‘[m]onstrous, un-Christianlike, un-English” to “pass upon her… the sentence of excommunication… and empty the vial of social wrath upon her,’ particularly when prostitution was often ‘an industry and a resource against hunger’ (Acton 1857: 5, 183). Only a few years later in 1864, Parliament passed the Contagious Diseases Act, which sought to curb the prevalence of venereal diseases in the British Military by arresting any woman thought to be a prostitute, and forcing her to submit to a medical exam. If she had a venereal disease, she was sent to a hospital, and if she refused the exam or hospitalization, ‘she could be imprisoned with or without hard labor’ (Hamilton 1978: 14). Even women who were not prostitutes hardly fared better under British law when it came to sexual assault. A study of Kent County from 1859-1880 shows ‘only 21 percent of men accused of rape stood trial for that offense’ and women who came forward were ‘blamed for failing to protect their innocence from “normal’’ male impulses’ (Conly 1986: 521, 536). Women who were forced to become ‘fallen’ could still be shamed, while men often faced little or no consequences for their actions.

‘Goblin Market’ critiques these clear double standards of sex and sexual degradation. When Laura becomes ill after eating the goblin fruit, ‘Her hair grew thin and grey;/ She dwindled, as the fair full moon doth turn/ To swift decay and burn’ (Rossetti 1862). These symptoms are emblematic of syphilis, a venereal disease which often affected prostitutes, as well as philandering men and their unsuspecting wives. Critics against the Contagious Diseases Act often spoke ‘about profligate men bringing venereal disease into respectable marriages’ (Townsend 2018: 79). Laura merely buys a piece of fruit and suffers unforeseen repercussions, paralleling innocent women enduring consequences like venereal diseases as a result of men’s actions. ‘Goblin Market’ also addresses the horror of sexual assault when the goblins attack Lizzie after she refuses their advances: ‘They trod and hustled her,/ Elbow’d and jostled her,/ Claw’d with their nails’ and ‘[t]ore her gown and soil’d her stocking’ (Rossetti 1862). This vicious attack on Lizzie’s person is interpreted as attempted rape, reiterating the pain and injury that men could level on women both physically with diseases and assault, and metaphorically through the labeling and shaming of women as ‘fallen.’

Working to alter this fallen woman narrative of pain and death, Rossetti’s strategic use of fantasy and poetry reclaims these genres and modes for women and women readers. Men had always dominated the genre and profession of poetry; but fairy-tale authors such as the Brothers Grimm and Scottish folklorist Andrew Lang took many of their stories from women around them. Marina Warner writes that ‘the Grimm Brothers’ most inspiring and prolific sources were women, from families of friends to close relations’ (1994: 19, 20). Andrew Lang ‘relied on his wife Leonora Alleyne, as well as a team of women editors, transcribers, and paraphrasers’ to produce his popular fairy books (Warner 1994: 20, 21). Fairy tales, so often passed from one generation of women to the next, were now being retold by male authors, often in ways that emphasized misogyny, with women depicted as submissive or villainous.

Rossetti’s poem therefore reclaims poetry and fantasy as a method to communicate with women readers about the severe topic of sex and the fallen woman. Poetry, often thought of as an aesthetic mode, was employed in the nineteenth century as a platform to discuss ‘issues of politics, gender and epistemology…’ (Armstrong 1993: 10). Fairy tales were also a means of relating controversial topics, as ‘it helps us to see [the] actual world [by visualizing] a fantastic one’ (Warner 1994: XVI). Following the tradition of fairy tales as messages to women readers, ‘Goblin Market’ rejects the notion of women becoming instantly ruined if they were classified as a ‘fallen woman.’ After Laura arrives back home after eating the goblin fruit, she and Lizzie are described as ‘Like two blossoms on one stem/ Like two flakes of new-fall’n snow/ Like two wands of ivory’ (Rossetti). Though Laura has eaten the fruit, while Lizzie has not, ‘Rossetti presents them in a way that suggests duplication’ (Bernhard-Jackson 2017: 454). This language of duplication, with the repetition of ‘like two,’ emphasizes there is no difference between ‘pure’ Lizzie and ‘fallen’ Laura. The use of white imagery further highlights their similarity: ‘new-fall’n snow,’ and ‘wands of ivory’ are symbols of sexual purity and innocence, indicating that Laura has not immediately been altered by consuming the fruit. Instead of being ‘a woman with half the woman gone,’ Laura remains as pure as Lizzie, contrasting with the literary trope that the loss of a woman’s sexual innocence brings a sudden transformation into either a creature of vice or despair (Acton 1857: 166).

‘Goblin Market’ further expresses the role men play in the seduction of women, rather than solely blaming women for giving in to desire. Laura initially resists the goblin’s call. ‘We must not look at goblin men,/ We must not buy their fruits’ she warns Lizzie, aware of the dangers of the goblins (Rossetti 1862). However, the goblins work together to sell their wares to the cautious Laura by displaying a sweet facade, as ‘[s]he heard a voice like voice of doves/ Cooing all together:/ They sounded kind and full of loves…’ (Rossetti 1862). The stanza exhibits the deceptive and manipulative nature of the goblins, representing experienced men flattering unsuspecting women. Acton wrote in his report ‘Many [women]—far more than would generally be believed—fall from pure unknowingness’ (1857: 32). Rossetti’s work supports this statement, rejecting the standard narrative that Laura is fully responsible for her fall. Instead, it asserts that men also play a significant part.

Along with warning women about the dangers of men, as in any fairy tale, Rossetti ends her story with a message. The behavior of the goblins directly mimics the cruelty and mistreatment Victorian women could suffer at the hands of men. Rossetti asserts that as men injure women in pursuit of personal pleasure, women must rise up to protect members of their sex. In Rossetti’s fairy tale, Laura survives, and she and Lizzie become wives, ‘With children of their own;’, and the final lesson she imparts to their children is that ‘there is no friend like a sister/ In calm or stormy weather;/ To cheer one on the tedious way,/ To fetch one if one goes astray,/ To lift one if one totters down,/ To strengthen whilst one stands’ (Rossetti 1862). The emphasis on sisters refers not only to Laura and Lizzie, but also to the ‘sisterhood’ between all women, expressing the need to protect and uplift one another rather than participate in the shaming and social exiling of fallen women. The lines ‘fetch if one goes astray/ To lift one if one totters down,’ further argues that while women may ‘stumble’ from ideals of sexual purity, they can still be redeemed and live successful lives, as demonstrated by Laura.

Thus, Rossetti alters the traditional fallen woman narrative from a story of pain and grief to one of redemption and encouragement. If a woman strayed outside of sexual purity, she was destroyed by her society—her reputation was ruined, and the literary figure of the fallen woman usually died for her transgressions. However, Rossetti reclaims female traditions of fairy tales and poetry from male canon, writing her own fairy tale to communicate to her female audience. Laura only lives because of Lizzie’s efforts, informing women that they need to protect and aid women like Laura, rather than shaming them. ‘Goblin Market’ is therefore a call to arms for women to rise up and defend their fellow women from the stigma and humiliation so often thrust upon them by men.

Bibliography

Acton, William. 1857. Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects (London: John Churchill, New Burlington Street)

Armstrong, Isobel. 1993. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poets, and Politics (London: Routledge)

Bernard-Jackson, Emily A. 2017. ‘“Like Two Pigeons in One Nest, Like Two Seedlings in One Capsule”: Reading Goblin Market in Conjunction with Victorian Twin Discourse’, Victorian Poetry, 55.4: 451-470

Conley, Carolyn A. 1986. ‘Rape and Justice in Victorian England.’ Victorian Studies, 29. 4: 519–536

Hamilton, Margaret. 1978. ‘Opposition to the Contagious Diseases Acts, 1864-1886.’ Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 10.1: 14–27

Rossetti, Christina. 1862. “Goblin Market.” Poetry Foundation. <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44996/goblin-market> [accessed 20 October 2020]

Townsend, Joanne. 2018. ‘Marriage, Motherhood and the Future of the Race: Syphilis in Late- Victorian and Edwardian Britain’, in Syphilis and Subjectivity: From the Victorians to the Present, ed. by Kari Nixon and Lorenzo Servitje (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), pp. 67-89

Warner, Marina. 1994. From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and their Tellers (London: Chatto & Windus)

Promoting the Gentle Man (Essay)

Final essay written for the course “The Fantastic History of the 20th Century” at the University of Glasgow. Please note all formatting, spelling, and punctuation is in accordance with U.K. requirements.

Promoting the Gentle Man: Representations of Masculinity in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Angela Carter’s ‘The Bloody Chamber’

The Lord of the Rings trilogy (1954-55) by J.R.R. Tolkien is renowned as one of the greatest examples of fantasy literature, serving as a template for many fantastic works that have followed it. However, Tolkien’s novels are often critiqued for their lack of female characters. Contrastingly, Angela Carter’s feminist reimagining of fairy tales in short stories such as ‘The Bloody Chamber’ from The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories (1979) utilizes almost exclusively female perspectives to explore themes of sexuality, femininity, and patriarchy. Though these works were written decades apart, in dissimilar styles, and are different kinds of fantasy works, they each explore subversions of masculinity.

Notable works of scholarship examine representations of gender in each of these works individually, such as Beatriz Ruiz’s ‘J.R.R. Tolkien’s Construction of Multiple Masculinities in The Lord of the Rings’ and Caleb Sivyer’s ‘A Scopophiliac Fairy Tale: Deconstructing Normative Gender in Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber”’. However, this essay appears to be the first to discuss how fantasy affords particular ways of constructing masculinity by comparing these two texts. Employing definitions and conventions of the fantasy genre from Rosemary Jackson’s Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion (1981) and Farah Mendlesohn’s Rhetorics of Fantasy (2008), this essay will first discuss the different categories of fantasy individually associated with The Lord of the Rings and ‘The Bloody Chamber’, and how they affect their approaches of examining gender. Then, it will assess how they each undermine ideas of Western traditional masculinity to promote a vision of a gentler, more humble man, with Tolkien’s rooted in ideals of love as power, and Carter’s as an upheaval of dominant patriarchy to a figure who offers support and companionship, rather than control.

The different subgenres of fantasy of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Carter’s ‘The Bloody Chamber’ allow them to examine masculinity through their own unique methods. Tolkien’s Middle Earth saga falls into what Rosemary Jackson describes as the ‘marvellous’ in her book Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. Jackson explains that ‘a marvellous realm’, such as Middle Earth, ‘transports the reader […] into an absolutely different, alternative world, a “secondary” universe’ (Jackson 1981: 25). She goes on to explain that ‘This [secondary universe] is relatively autonomous, relating to the “real” through metaphorical reflection and never, or rarely, intruding [into it]’ (Jackson 1981: 25). This definition of the ‘marvellous’ expresses that the fantastic world of Middle Earth only has minor, if any, relations to our reality, or the ‘real’ world. Operating as a separate universe, it allows readers to reconsider aspects of their own society through disassociation. In other words, immersion in Tolkien’s Middle Earth allows us to reflect on our own society and its norms in a new light. As Brian Attebery explains, Tolkien ‘thought fantasy could restore [familiar objects] to the vividness with which we first saw them’ (Attebery 1992: 16). Therefore, ‘familiar’ conventions, such as gender, are viewed by readers with a new perspective when presented with Tolkien’s ideas of masculinity through the characters of Middle Earth.

Moreover, The Lord of the Rings’s status as a quest fantasy further encourages readers to observe the world and its norms through an original and unfamiliar position. Farah Mendlesohn categorizes Tolkien’s series as a ‘portal-quest fantasy’, meaning that ‘a character leaves [their] familiar surroundings and passes through a portal to an unknown place’ (2008: 1). In the case of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo and the other hobbits leave the safety of the Shire and travel across the vast land of Middle Earth. Readers of the novels are associated with the hobbits, as both have never journeyed beyond the peaceful valley of the Shire introduced at the start of the series. This reflects Mendlesohn’s explanation that in portal-quest fantasies ‘[t]he position of the reader [...] is one of companion-audience, tied to the protagonist, and dependent upon the protagonist for explanation’ (Mendlesohn 1). Readers, like Frodo, do not know what to expect of the peoples and lands that lie outside the Shire, designated on Frodo’s maps as the ‘mostly white spaces beyond its borders’ (Tolkien 2020: 43). Everything Frodo and his companions encounter in Middle Earth is new and strange to them. Thus, when readers are introduced to male characters along their journey, it is through the voyeurism of meeting these entities for the first time, prompting them to engage with perspectives and ideas of gender exhibited by cultures that are unfamiliar to hobbits, and thus to human readers by proxy.

Angela Carter’s ‘The Bloody Chamber’ similarly disassociates readers from preconceived notions of masculinity, but through the use of a fairy tale retelling with grotesque and fantastic elements. The short story has been categorized as ‘dark fantasy’, or a fantasy ‘which incorporates a sense of horror’ and in which ‘protagonists believe themselves to inhabit a world of consensual mundane reality and learn otherwise [...] [living] with new knowledge’ (Kaveney 2012: 214, 218). This definition fits Carter’s ‘The Bloody Chamber’, a reimagining of the Bluebeard fairy-tale, wherein the newlywed narrator discovers her husband, the wealthy Marquis, has murdered his previous three wives. Carter’s use of the grotesque throughout the short story also reflects many aspects of horror. The scene where the narrator finds the bodies of her husband’s former wives evokes vivid and terrifying imagery of bodily trauma. For example, the narrator describes that one of the wives has been reduced to ‘a skull, so utterly denuded, now, of flesh, that it scarcely seemed possible the stark bone had once been richly upholstered with life [...] strung up by a system of unseen cords, so that it appeared to hang disembodied’ (Carter 1993: 16, 17).

The story also exemplifies Jackson’s definition of the ‘fantastic’. As Jackson explains:

Fantastic narratives confound elements of both the marvellous and the mimetic. They assert that what they are telling is real—relying upon all the conventions of realistic fiction […] then they […] break that assumption of realism by introducing what […] is manifestly unreal. (Jackson 1981: 20)

Carter’s tale utilizes this blend of ‘the marvellous and the memetic’, or fantasy and realism, as the story is written in a realistic style, and set in the early twentieth century. While the majority of the story takes place in the Marquis’s castle, there are also cars, electricity, running water, and telephones. Fused with this familiar technology are ‘unreal’ elements that make the story a fantastic narrative. Two examples of the ‘marvellous’ are associated with the bloody key, which reveals to the Marquis that the narrator has entered the deadly chamber she promised him she would avoid. The gory evidence will not wash away: ‘The bloody token stuck [...] the more I scrubbed the key, the more vivid grew the stain’ (Carter 1993: 20). Moreover, after her husband presses the key to her forehead, the mark remains there forever, as ‘No paint nor powder […] can mask that red mark’ (Carter 1993: 26). These ‘unreal’ elements, combined with the horror and Carter’s grotesque descriptions, serve to ‘pull the reader from the apparent familiarity and security of the known and everyday world’ (Jackson 1981: 20). Though it does not take place in a separate fantasy land, Carter still creates a sense of disassociation from reality, prompting readers to reassess constructions and ideals of masculinity within her story of marital murder and abuse.

One of the ways in which both The Lord of the Rings and ‘The Bloody Chamber’ re-evaluate traditional masculinity is by presenting its severe and fundamental flaws, then subverting it in favour of more sympathetic male figures. Tolkien clearly esteems characters such as the hobbit Samwise Gamgee over conventional warrior-figures such as Boromir. Beatriz Ruiz writes that there is a pattern of characters in Tolkien’s series that encompasses ‘a traditional dominant hegemonic masculinity’ (2017: 26) based on hypermasculinity, which is in part defined by viewing ‘violence as manly, and danger as exciting’ (Mosher and Sirkin 1984: 151). Boromir meets these standards, as he is established throughout The Fellowship of the Ring by his prowess and pride as a fighter. When the Ring tempts Boromir to take it from Frodo, it gives him a vision of might and victory in battle: ‘The Ring would give me power of Command. How I would drive the hosts of Mordor, and all men would flock to my banner!’ (Tolkien 2020: 398). Boromir’s masculinity is therefore based in his strength and ability to fight and lead, and while it is rooted in offering protection, it also becomes his greatest weakness, as ‘[t]he Ring [...] [plays] on his wish to save his country and on his desire for personal glory” (Hammond and Scull 2005: 349). Characteristics of physical strength and pride, normally thought of in Western culture as admirable masculine qualities, instead become Boromir’s undoing, reflecting Tolkien’s belief that a new kind of masculinity needed to take its place.

This new, better masculinity is defined by characters such as Sam. As Brian Attebery writes, ‘the genre of fantasy has become a space for cultural negotiation,’ allowing Tolkien to confront ideas of traditional masculinity by presenting male characters like Sam as the greatest heroes in Middle Earth (2014: 21). Jane Chance writes that ‘[h]umility in Tolkien is always ultimately successful’ (2001: 41), and Ruiz explains that figures like Sam are defined by ‘their will to preserve life and their peaceful attitudes’ (2017: 30). This emphasis on humility, peace, and conservation contrasts with typical male bravado in fighting and killing. Without Sam and his devotion to Frodo, Frodo might not have been able to destroy the Ring. He carries Frodo the last stretch up Mount Doom, exclaiming, ‘“I can't carry [the Ring] for you, but I can carry you!”’ (Tolkien 2012: 940). Moreover, when Sam is tempted by the Ring, he, unlike Boromir, is able to resist its visions: ‘In that hour of trial it was his love of his master that helped most to hold him firm; but also deep down in him lived still unconquered his plain hobbit-sense’ (Tolkien 2012: 901). Desires for glory and power, though they exist in Sam, cannot conquer his greatest qualities: his love and common sense. Due to his caring and humility, Sam is able to save Middle Earth, and live a prosperous life in the Shire with a wife and children. Before he leaves Middle Earth, Frodo tells Sam, ‘[y]our hands and your wits will be needed everywhere. You will be the Mayor, of course, as long as you want to be, and the most famous gardener in history’ (Tolkien 2012: 1029). Sam’s intelligence is viewed as vital to the Shire, but also his care and ability to foster new growth, and therefore new beginnings, as a gardener.

This view on masculinity is directly influenced by Tolkien’s experiences in both World War I and II. The subversion of ‘warrior men’ reflects Tolkien’s service in World War I as a young man, and he knew from personal experience that there was no glory in war or battle. As Benvenuto remarks, ‘although not a “pacifist” in modern terms, Tolkien grew to detest [war], as he knew firsthand the pain and misery it wreaked on people’ (2006: 50). By the end of World War II, Britain had ‘suffered 264,433 military and 60,595 civilian deaths’ and ‘[o]ne in three houses had been destroyed by bombing’ (BBC 2020: 5 and 6 of 11 paras). In this post-war world, there was not a need for men seeking further aggression, but those like Sam, who would bring restoration and life back into a ravaged and weary Britain. As Mendlesohn explains, ‘The Lord of the Rings is not a quest for power, but a journey to destroy power’, in the traditional understanding of it as dominion over others (2008: 4). The one ‘good choice’ of power in the series is ‘the Christ-like power of love, healing, and gentleness’ (Enright 2007: 26 of 26 paras), therefore moving away from a masculinity that seeks domination and violence, in favour of a masculinity that instead values altruism and peacemakers. Mendlesohn explains that ‘Fantasy relies on a moral universe’ making it a ‘sermon on the way things should be’ (2008: 5). By presenting love and humility as the qualities of the greatest heroes and admired characters to those exploring Middle Earth, Tolkien grants readers a new outlook on what traits should be valued and upheld in all men.

In a similar manner to Tolkien, Carter’s contrast between the Marquis, or ‘Bluebeard’, and the piano tuner, Jean-Yves, favours the figure of a kind man over one of overt sexual and violent masculinity. Like Boromir, the Marquis follows the definition of ‘hypermasculinity’ in that he relishes violence, but he also fulfils its third aspect, as he possesses ‘[callous] sex attitudes toward women’ (Mosher and Sirkin 1984: 151). He not only owns a collection of pornographic books, but the way he gazes at the narrator constantly makes her feel both vulnerable and hypersexualized. As Caleb Sivyer remarks, the ‘Marquis represents the dominant scopic position within patriarchal society: the active, gazing position’ (2013: 48). The narrator explains ‘I saw him watching me […] with the assessing eye of a connoisseur inspecting horseflesh’, and she is shocked by the ‘sheer carnal avarice of [his gaze]’ (Carter 1993: 5). The Marquis dehumanizes the narrator simply by his look, transforming her from a woman into mere flesh, an object of consumption for his sexual desire. But the Marquis’s sexual appetite is also linked to his masculine love of violence, as he tells the narrator he will kill her by ‘“Decapitation,” he whispered, almost voluptuously’ (Carter 1993: 22). He takes a sadomasochistic pleasure from murder, exemplifying how the fantastic pulls the reader from the ‘security and known of the everyday’ to experience the narrator’s fear and disgust at the Marquis’s traditional masculinity (Jackson 1981: 20).

However, the Marquis’s violent masculinity brings him a violent death at the hands of the narrator’s mother, who arrives just in time to save her daughter. The mother is presented as a fantastic figure: ‘You never saw such a wild thing as my mother, her hat seized by the winds and blown out to sea so that her hair was her white mane, [...] one hand on the reins of the rearing horse while the other clasped my father's service revolver’ (Carter 1993: 25). This description of the mother makes her an otherworldly being, ferocious and unafraid to defend her daughter. The Marquis ‘[wields an] honourable sword as if it were a matter of death or glory’ (Carter 1993: 25) as he tries to attack, but the narrator’s mother ‘[raises her] father’s gun, took aim and put a single, irreproachable bullet through [his] head’ (Carter 1993: 25, 26). While demonstrating a mother’s love, the fantastic death of the Marquis also symbolizes a revolt against the patriarchal oppression of traditional masculinity, which not only promotes brutality but sexual exploitation.

Contrastingly, Jean-Yves, like Tolkien’s Sam, is a humble soul, characterized by his tender nature. A blind man, the narrator introduces him as ‘young, with a gentle mouth and grey eyes’ (Carter 1993: 12). Sivyer writes that Jean-Yves’s blindness ‘can be read as offering an alternative to the economy of the violent male gaze, as represented by the husband’ (2013: 47). His blindness also ‘forces his hearing to become more proficient [...] encouraging qualities of receptiveness and attentiveness’ (Sivyer 2013: 59). As opposed to the Marquis, the narrator says, ‘his eyes were singularly sweet’ (Carter 1993: 18). He does not value the narrator’s physical appearance or body, but rather her musical ability. But more than an admirer of her talent, he displays self-sacrificing bravery and loyalty. When the narrator is summoned by her husband to be killed, Jean-Yves chooses to accompany her, saying, ‘“I can be of some comfort to you [...] Though not much use.”’ (Carter 1993: 23). While the Marquis declares he will kill Jean-Yves as well, Jean-Yves does not allow the narrator to face the Marquis alone. But through his love for the narrator, Jean-Yves becomes her lover, and helps the narrator run a music school. This addition of Jean-Yves to the story demonstrates further favour of his courage and humble qualities, as he is not featured in the original Bluebeard narrative. Yet in this iteration, he comforts the narrator, offering an alternative love and masculinity based in kindness and personal value which is rewarded, rather than one of dominance and fear that has to be destroyed.

This stark contrast between Jean-Yves’s gentleness and the Marquis’s pornographic violence subverts traditional masculinity, presenting Jean-Yves as the desirable model of manhood for a world of social equality. As Jackson explains, ‘It is no accident that so many [women] writers [...] have all employed the fantastic to subvert patriarchal society—the symbolic order of modern culture’ (Jackson 1981: 61). In Carter’s case, the fantastic destroys the patriarchal through the appearance of the narrator’s mother, who senses through ‘the maternal telepathy’ that something was wrong, and kills the Marquis (Carter 1993: 26). Revolt against such patriarchy, as represented by traditional masculinity, was a key feature of second-wave feminism, which sought ‘social equality regardless of sex’ during the period of Carter’s writing (Rampton 2008: 5 of 20 paras). To create this world of social equality therefore requires men like Jean-Yves who offer kindness and companionship to women, instead of those who murder and repress like the Marquis.

Thus, Tolkien and Carter challenge norms of masculinity through their fantasy works. Though Tolkien’s Middle Earth is a separate fantasy realm, while Carter’s story is a fantastic narrative of real and magical elements, the two similarly challenge norms of traditional masculinity. Tolkien highlights the weaknesses of aggressive warriors like Boromir, and Carter displays the violence and horrific sexual obsession of the Marquis. The evils of such masculinity are contrasted with the ideal of a better man, whose characteristics of humility and gentleness are displayed in the characters of Samwise Gamgee and Jean-Yves. Though appearing vastly different, both texts prove how fantasy continues to challenge conventions such as gender, no matter through what mode or subgenre.

Bibliography

Attebery, Brian. 2014. Stories about Stories: Fantasy and the Remaking of Myth (New York: Oxford University Press)

Attebery, Brian. 1992. Strategies of Fantasy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

Benvenuto, Raffaella M. 2006. ‘Against Stereotype: Éowyn and Lúthien as 20th-Century Women’, in Tolkien and Modernity, ed. by Frank Weinreich and Thomas Honegger. (Zollikofen, Switzerland: Walking Tree) pp. 31-54

British Broadcasting Corporation. 2020. ‘Age of Austerity’, BBC <https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zgmf2nb/revision/1> [Accessed 8 December 2020]: 11 paragraphs

Carter, Angela. 1993. The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories (New York City: Penguin)

Chance, Jane. 2001. The Lord of the Rings: The Mythology of Power (Lexington: UP of Kentucky)

Enright, Nancy. 2007. ‘Tolkien’s Females and the Defining of Power’, Renascence: Essays on Value in Literature, 59.2, 26 paragraphs

Fredrick, Candice and Sam McBride. 2001. Women Among the Inklings: Gender, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams (London: Greenwood Press)

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull. 2005. The Lord of the Rings. A Reader’s Companion (London: HaperCollins)

Jackson, Rosemary. 1981. Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion (London: Routledge)

Kaveney, Roz. 2012. ‘Dark Fantasy and Paranormal Romance’, in The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature, ed. by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press)

Mendlesohn, Farah. 2008. Rhetorics of Fantasy (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press)

Mosher, Donald L. and Mark Sirkin. 1984. ‘Measuring a Macho Personality Constellation’, Journal of Research in Personality 18: 150–163.

Rampton, Martha. 2008. ‘Four Waves of Feminism’, Pacific Magazine <https://www.pacificu.edu/magazine/four-waves-feminism> [Accessed 9 December 2020]: 20 paragraphs