'There is no Friend Like a Sister’: The Reclamation of the Fallen Woman in ‘Goblin Market’ (Essay)

Originally written as a midterm essay for the course “Realism and Fantasy in Victorian Literature” at the University of Glasgow in Fall 2020. Please note all spelling, punctuation, and citations are formatted according to requirements at universities in the United Kingdom.

‘There is no Friend Like a Sister’: The Reclamation of the Fallen Woman in ‘Goblin Market’

Christina Rossetti’s ‘Goblin Market’ (1859) remains one of the most striking examples of Victorian fantasy and sisterhood. However, ‘Goblin Market’ serves as more than just an unnerving and entertaining tale—it represents the reclamation of the fallen woman narrative, and a departure from male-dominated voices and canon in poetry and fantasy. This essay explores how Rossetti’s poem critiques social efforts during the 1850s and 1860s that purposefully blamed and controlled women. Then, it demonstrates how ‘Goblin Market’ moves away from male control, both in its form and utilization of fantasy, before concluding that in a male-dominated society that seeks to destroy women and their reputations, it is women who must step forward to protect their fellow sisters.

When ‘Goblin Market’ was published in 1862, numerous discussions and debates were occurring about women and sexuality, with topics ranging from prostitution to sexual assault. In 1857, William Acton published Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects, offering one of the first pragmatic reports on prostitution in mid-nineteenth century England. As opposed to believing prostitutes were irrevocably immoral, he took a more sympathetic stance to their plight, arguing it was ‘[m]onstrous, un-Christianlike, un-English” to “pass upon her… the sentence of excommunication… and empty the vial of social wrath upon her,’ particularly when prostitution was often ‘an industry and a resource against hunger’ (Acton 1857: 5, 183). Only a few years later in 1864, Parliament passed the Contagious Diseases Act, which sought to curb the prevalence of venereal diseases in the British Military by arresting any woman thought to be a prostitute, and forcing her to submit to a medical exam. If she had a venereal disease, she was sent to a hospital, and if she refused the exam or hospitalization, ‘she could be imprisoned with or without hard labor’ (Hamilton 1978: 14). Even women who were not prostitutes hardly fared better under British law when it came to sexual assault. A study of Kent County from 1859-1880 shows ‘only 21 percent of men accused of rape stood trial for that offense’ and women who came forward were ‘blamed for failing to protect their innocence from “normal’’ male impulses’ (Conly 1986: 521, 536). Women who were forced to become ‘fallen’ could still be shamed, while men often faced little or no consequences for their actions.

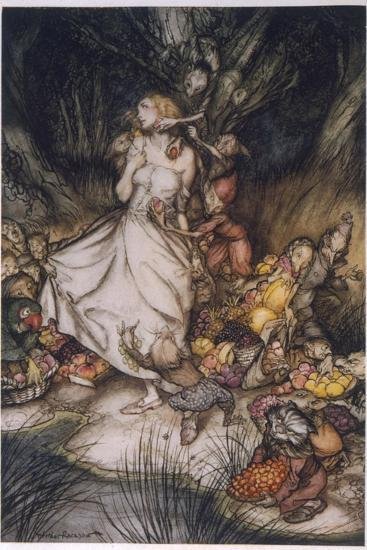

‘Goblin Market’ critiques these clear double standards of sex and sexual degradation. When Laura becomes ill after eating the goblin fruit, ‘Her hair grew thin and grey;/ She dwindled, as the fair full moon doth turn/ To swift decay and burn’ (Rossetti 1862). These symptoms are emblematic of syphilis, a venereal disease which often affected prostitutes, as well as philandering men and their unsuspecting wives. Critics against the Contagious Diseases Act often spoke ‘about profligate men bringing venereal disease into respectable marriages’ (Townsend 2018: 79). Laura merely buys a piece of fruit and suffers unforeseen repercussions, paralleling innocent women enduring consequences like venereal diseases as a result of men’s actions. ‘Goblin Market’ also addresses the horror of sexual assault when the goblins attack Lizzie after she refuses their advances: ‘They trod and hustled her,/ Elbow’d and jostled her,/ Claw’d with their nails’ and ‘[t]ore her gown and soil’d her stocking’ (Rossetti 1862). This vicious attack on Lizzie’s person is interpreted as attempted rape, reiterating the pain and injury that men could level on women both physically with diseases and assault, and metaphorically through the labeling and shaming of women as ‘fallen.’

Working to alter this fallen woman narrative of pain and death, Rossetti’s strategic use of fantasy and poetry reclaims these genres and modes for women and women readers. Men had always dominated the genre and profession of poetry; but fairy-tale authors such as the Brothers Grimm and Scottish folklorist Andrew Lang took many of their stories from women around them. Marina Warner writes that ‘the Grimm Brothers’ most inspiring and prolific sources were women, from families of friends to close relations’ (1994: 19, 20). Andrew Lang ‘relied on his wife Leonora Alleyne, as well as a team of women editors, transcribers, and paraphrasers’ to produce his popular fairy books (Warner 1994: 20, 21). Fairy tales, so often passed from one generation of women to the next, were now being retold by male authors, often in ways that emphasized misogyny, with women depicted as submissive or villainous.

Rossetti’s poem therefore reclaims poetry and fantasy as a method to communicate with women readers about the severe topic of sex and the fallen woman. Poetry, often thought of as an aesthetic mode, was employed in the nineteenth century as a platform to discuss ‘issues of politics, gender and epistemology…’ (Armstrong 1993: 10). Fairy tales were also a means of relating controversial topics, as ‘it helps us to see [the] actual world [by visualizing] a fantastic one’ (Warner 1994: XVI). Following the tradition of fairy tales as messages to women readers, ‘Goblin Market’ rejects the notion of women becoming instantly ruined if they were classified as a ‘fallen woman.’ After Laura arrives back home after eating the goblin fruit, she and Lizzie are described as ‘Like two blossoms on one stem/ Like two flakes of new-fall’n snow/ Like two wands of ivory’ (Rossetti). Though Laura has eaten the fruit, while Lizzie has not, ‘Rossetti presents them in a way that suggests duplication’ (Bernhard-Jackson 2017: 454). This language of duplication, with the repetition of ‘like two,’ emphasizes there is no difference between ‘pure’ Lizzie and ‘fallen’ Laura. The use of white imagery further highlights their similarity: ‘new-fall’n snow,’ and ‘wands of ivory’ are symbols of sexual purity and innocence, indicating that Laura has not immediately been altered by consuming the fruit. Instead of being ‘a woman with half the woman gone,’ Laura remains as pure as Lizzie, contrasting with the literary trope that the loss of a woman’s sexual innocence brings a sudden transformation into either a creature of vice or despair (Acton 1857: 166).

‘Goblin Market’ further expresses the role men play in the seduction of women, rather than solely blaming women for giving in to desire. Laura initially resists the goblin’s call. ‘We must not look at goblin men,/ We must not buy their fruits’ she warns Lizzie, aware of the dangers of the goblins (Rossetti 1862). However, the goblins work together to sell their wares to the cautious Laura by displaying a sweet facade, as ‘[s]he heard a voice like voice of doves/ Cooing all together:/ They sounded kind and full of loves…’ (Rossetti 1862). The stanza exhibits the deceptive and manipulative nature of the goblins, representing experienced men flattering unsuspecting women. Acton wrote in his report ‘Many [women]—far more than would generally be believed—fall from pure unknowingness’ (1857: 32). Rossetti’s work supports this statement, rejecting the standard narrative that Laura is fully responsible for her fall. Instead, it asserts that men also play a significant part.

Along with warning women about the dangers of men, as in any fairy tale, Rossetti ends her story with a message. The behavior of the goblins directly mimics the cruelty and mistreatment Victorian women could suffer at the hands of men. Rossetti asserts that as men injure women in pursuit of personal pleasure, women must rise up to protect members of their sex. In Rossetti’s fairy tale, Laura survives, and she and Lizzie become wives, ‘With children of their own;’, and the final lesson she imparts to their children is that ‘there is no friend like a sister/ In calm or stormy weather;/ To cheer one on the tedious way,/ To fetch one if one goes astray,/ To lift one if one totters down,/ To strengthen whilst one stands’ (Rossetti 1862). The emphasis on sisters refers not only to Laura and Lizzie, but also to the ‘sisterhood’ between all women, expressing the need to protect and uplift one another rather than participate in the shaming and social exiling of fallen women. The lines ‘fetch if one goes astray/ To lift one if one totters down,’ further argues that while women may ‘stumble’ from ideals of sexual purity, they can still be redeemed and live successful lives, as demonstrated by Laura.

Thus, Rossetti alters the traditional fallen woman narrative from a story of pain and grief to one of redemption and encouragement. If a woman strayed outside of sexual purity, she was destroyed by her society—her reputation was ruined, and the literary figure of the fallen woman usually died for her transgressions. However, Rossetti reclaims female traditions of fairy tales and poetry from male canon, writing her own fairy tale to communicate to her female audience. Laura only lives because of Lizzie’s efforts, informing women that they need to protect and aid women like Laura, rather than shaming them. ‘Goblin Market’ is therefore a call to arms for women to rise up and defend their fellow women from the stigma and humiliation so often thrust upon them by men.

Bibliography

Acton, William. 1857. Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects (London: John Churchill, New Burlington Street)

Armstrong, Isobel. 1993. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poets, and Politics (London: Routledge)

Bernard-Jackson, Emily A. 2017. ‘“Like Two Pigeons in One Nest, Like Two Seedlings in One Capsule”: Reading Goblin Market in Conjunction with Victorian Twin Discourse’, Victorian Poetry, 55.4: 451-470

Conley, Carolyn A. 1986. ‘Rape and Justice in Victorian England.’ Victorian Studies, 29. 4: 519–536

Hamilton, Margaret. 1978. ‘Opposition to the Contagious Diseases Acts, 1864-1886.’ Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 10.1: 14–27

Rossetti, Christina. 1862. “Goblin Market.” Poetry Foundation. <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44996/goblin-market> [accessed 20 October 2020]

Townsend, Joanne. 2018. ‘Marriage, Motherhood and the Future of the Race: Syphilis in Late- Victorian and Edwardian Britain’, in Syphilis and Subjectivity: From the Victorians to the Present, ed. by Kari Nixon and Lorenzo Servitje (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), pp. 67-89

Warner, Marina. 1994. From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and their Tellers (London: Chatto & Windus)